When I initially wrote A Gentle Feast, I did not include history. It isn’t that I believe history is unimportant. It is, in fact, my favorite subject and I believe it is supremely important. The struggle came from wrapping my brain around Miss Mason’s approach to history. Amongst homeschoolers, there is much a do about history, isn’t there? So many curriculums, so many cycles, so many books, so many “right” approaches. I was quite honestly intimidated to take on such a formidable subject. But as I read and researched Miss Mason’s writings, the PNEU (Parent’s National Education Union) programmes, and the Parent’s Review articles, I found myself drawn into this approach, as it resonated with my experience both as a teacher and a history lover. Miss Mason’s approach to history is quite unique amongst history curriculums on today’s homeschool market. It doesn’t fit into the nice 4-year cycle that I was led to believe was the ONLY way to properly lead students to have any accurate grasp of the pageant of human events.

I will attempt in this post to explain my findings on the subject and give some insight as to how I approached history in A Gentle Feast. Miss Mason says a great deal, so I will only highlight a few points here:

History instruction should begin with the history of the child’s home country. For the PNEU this was, of course, the history of England. Since I live in America, it is the history of the United States. These lessons should include hero tales, biographies, and other living books that spur the child’s imagination.

Volume 1, pg. 281 “The early history of a nation is better fitted than its later records for the study of children, because the story moves on a few broad, simple lines; while statesmanship, so far as it exists, is no more than the efforts of a resourceful mind to cope with circumstances… In the early years, while there are no examinations ahead, and the children may yet go leisurely, let them get the spirit of history into them by reading, at least one old Chronicle written by a man who saw and knew something of what he wrote about and did not get it secondhand. These old books are easier and pleasanter reading than most modern works on history; because writers know little of the ‘dignity of history’; they purl along pleasantly as a forest brook, tell you ‘all about it’, stir your heart with the story of a great event, amuse you with pageants and shows, make you intimate with the great people, and friendly with the lowly. They are just the right thing for the children whose eager souls want to get at the living people behind the words of the history book, caring nothing at all about progress, or statutes, or about anything but the persons, for whose action history is, to the child’s mind, no more than a convenient state. A child who has been carried through a single old chronicler in this way has a better foundation than if he knew all the dates and names and facts that ever were crammed for examination.”

For Term 94 in her programme, she used the following for Form I (grades 1-3) SOURCE:

Form I

English History.

-

- Our Island Story,* Vol. I., by E. H. Marshall (Jack, 3/3), pp. 94-140. Mrs. Frewen Lord’s Tales from Canterbury* (Sampson Low, 1/6), pp. 37-73

- Our Island Story, Vol. I., pp. 94-140. [A second lesson to be taken on Saturday, 9.20-9.40, otherwise pages read with omissions.]

In Vol. 1, she discusses reading Tales from Westminster Abby and then taking the children to see these spots for themselves. I think this is one of the benefits of starting with your own country’s history. Opportunities for field trips to see the world of the past abound. My children have visited a log cabin like Lincoln lived in and spent a lesson in an old one room school house. They still talk about these trips (and others) which gave them tangible experiences and images of the past.

The first year of Form I was spent in this heroic age. Vol 1 pg. 284: “But every nation has its heroic age before authentic history begins: there were giants in the land in those days, and the child wants to know about them.”

These books used in Form I are of high literary quality and are read to the child. Vol 6 page 172: “The child of six in Ib has, not stories from English History, but a definite quantity of consecutive reading, say, forty pages in a term, from a well-written, well-considered, large volume which is also well-illustrated. Children can-not of course themselves read a book which is by no means written down to the ‘child’s level’ so the teacher reads and the children ‘tell’ paragraph by paragraph, passage by passage.”

In A Gentle Feast, I designed Form I (grades 1-3) to start with American History. They will learn about the heroes of this time through tall tales, picture book biographies, and Stories of Great Americans for Little Americans. I did not separate the first year of Form I like Miss Mason suggested but keep first graders in the same family rotation.

In Form II (grades 4-6), students added on the history of a neighboring country following the same chronological progression. They also started studying Ancient history. Form III (grades 7-8) follows this same pattern.

Vol 6 pg. 175: “Form II (ages 9 to 12) have a more considerable historical programme which they cover with ease and enjoyment. They use a more difficult book than in IA, an interesting and well-written history of England of which they read some fifty pages or so in a term. IIA read in addition and by way of illustration the chapters dealing with the social life of the period in a volume. We introduce children as early as possible to the contemporary history of other countries as the study of English history alone is apt to lead to a certain insular and arrogant habit of mind. Naturally we begin with French history and both divisions read from the First History of France, very well written, the chapter contemporary with the English history they are reading.”

“The study of ancient history which cannot be contemporaneous we approach through a chronologically-arranged book about the British Museum.”

For Term 94, she used:

Form II

English History.

A&B. A History of England,* by H.O. Arnold-Forster (Cassell, 8/6), pp. 131-201 (1154-1307). Black’s History Pictures (2/6 a set), may be used.

A. Scott’s Tales of a Grandfather (University Press, 2/3), pp. 66-106.

French History.

A. A First History of France,* by L. Creighton (Longmans, 5/-), pp. 45-81, to be contemporary with English History. Evaus’ Political War Map of Europe, Asia, Africa* (4d.)

B. Stories from French History, by E.C. Price (Harrap, 5/-), pp. 18-66.

General History.

A. The British Museum for Children,* by Frances Epps (P.N.E.U. Office, 3/6), chapter 12. Teacher study preface. Keep a book of Centuries (P.N.E.U. Office, 2/6), putting in illustrations from all the history studied during the term. The Ancient World,* by A. Malet (Hodder & Stoughton, 5/-) pp. 82-101.

Form III

English History.

Arnold Forster’s A History of England (Cassell, 8/6), pages 131-186 (1154-1307). Scott’s Tales of a Grandfather(University Press, 2/3), pp 84-106. Make a chart of the 12th Century (1100-1200), (see reprint from P.R., July, 1910, 3d.). Read the daily news and keep a calendar of events.

French History.

Creighton’s First History of France* (Longmans, 5/-) pp. 45-81 (1154-1307).

General History.

Read from De Joinville’s Chronicles of the Crusades* (Dens, 2/6). The British Museum for Children,* by Frances Epps (P.N.E.U. Office 3/8), Chapter 12. Teacher study preface. Keep a Book of Centuries* (P.N.E.U. Office, 2/6), putting in illustrations from all the history studied. Stories from Indian History (O.L.S.I.), Vol. 1., 2/-, pp. 1-25.

In A Gentle Feast, I added British history to be studied chronologically with American in Form II. I also added in stories for Ancient history. I also add in World History in Form III.

In Forms IV and up (high school) we see English history and General history (part contemporary world corresponding to the English history and part Ancient studies). In these forms, literature is highly integrated to the time period being studied.

Volume 6 pg. 177 “But any sketch of the history teaching in Form V and VI in a given period depends upon a notice of the ‘literature’ set; for plays, novels, essays, ‘lives’, poems are all pressed into service and where it is possible, the architecture, painting, etc, which the period produced.”

Here is the following programme from Term 94:

Form IV

English History.

Begin a chart of the 17th Century (1600-1700), (see reprint from P.R., July, 1910, 8d.). Read the daily news and keep a calendar of events. Gardiner’s History of England* (Longmans, 6/6), Vol. II., pp. 502-577 (1625-1680). A History of Everyday Things in England, by H. & O. Quennell (Batsford, 3/-), Part IV., may be used for period.

General History.

Medieval and Modern Times,* by T.R. Robinson. (Ginn & Co., 10/6) pp. 352-381 (1625-1660). Ancient Times: A History of the Early World,* by J. H. Breasted (Guinn, 10/6), pp. 140-220 (omit questions). Continue a Book of Centuries* (P.N.E.U. Office, 2/6), putting in illustrations from all history studied. Defoe’s Memoirs of a Cavalier* (University Press, 2/6), pp. 1-125

Form V and VI

English History

A Short History of the English People, by J. R. Green, Vol. I. (Dent, 2/6), (1625-1660).

General History.

VI. & V. Medieval and Modern Times, by J. H. Robinson (Ginn, 10/6), pp. 352-381 (1625-1660). Defoe’s Memoirs of a Cavalier (University Press, 2/6).

VI. Legacy of Greece and Rome, by W. de Burgh (Macdonald, 2/6), pp. 30-61.

V. Ancient Times: A History of the Early World, by J. H. Breasted (Ginn, 10/6), pp. 140-220 (omit questions).

Make summaries of dates and events. Use maps. Make charts. History Chart, by Lady Louise Loder (P.N.E.U. Office 5/-). A Pronouncing Dictionary of Mythology and Antiquities (Walker, 1/6). A Classical Atlas (Dent, 2/6).

We are not “responsible” for teaching every aspect of history to our children. We are given the task of preparing the feast from which our students may linger and imagine and progress at a leisurely pace, being firmly acquainted with the persons and places of a time well gone.

Volume 1 pg. 280: “The fatal mistake is the notion the he must learn outlines, or a baby edition of the whole history of England, or of Rome, just as he must cover the geography of ALL the world. Let him, on the contrary, linger pleasantly over the history of a single man, a short period, until he thinks the thoughts of that man, is at home in the ways of that period. Though he is reading and thinking of the lifetime of a single man, he is really getting intimately acquainted with the history of a whole nation for a whole age.”

Volume 6 pg. 178: “It is a great thing to possess a pageant of history in the background of one’s thoughts. We may not be able to recall this or that circumstance, but the imagination is warmed; we know that there is a great deal to be said on both sides of every question and are saved from crudities in opinion and rashness in action. The present becomes enriched for us with the wealth of all that has gone before.”

Narration is an integral component to history education. Narration can also be done through drawing and even playing.

Vol 6 pg. 172: “The teacher does not talk much and is careful never to interrupt a child who is called upon to ‘tell’. The first efforts may be stumbling but presently the children get into their stride and tell a passage at length with surprising fluency. The teacher probably allows other children to correct any faults in the telling when it is over… But she will bear in mind that the child of six has begun the serious business of this education, that it does not matter much whether he understands this word or that, but that it matters a great deal that he should learn to deal directly with books. Whatever a child or grown-up person can tell, that we may best sure he knows, and what he cannot tell, he does not know.”

Volume 1 pg.292: “History readings afford admirable material for narration, and children enjoy narrating what they have read or heard. They love, too, to make illustrations. Children who had been reading Julius Ceasar (and also, Plutarch’s Life), were asked to make a picture of their favourite scene, and the results showed the extraordinary power of visualizing, which the little people possess. Of course, that which they visualize, or imagine clearly, they know; it is a life possession. The drawings of the children in question are psychologically interesting as showing what various and sometimes obscure points appeal to the mind of child; and also, that children have the same intellectual pleasure as persons cultivated mind in working out new hints and suggestions…In these original illustrations (several of them by older children than those we have in view here), we get an example of the various images that present themselves to the minds of children during the readings of a great work; and a single such glimpse into a child’s mind convinces us of the importance of sustaining that mind using strong meat. Imagination does not stir at the suggestion of the feeble, much-diluted stuff that is too often put into children’s hands.”

Volume 1 pg. 294: “Children have other ways of expressing the conceptions that fill them when they are duly fed. They play at their history lessons, dress up, make tableaux, act scenes; or they have a stage, and their dolls act while they paint the scenery and speak the speeches. There is no end to the modes of expression children find when there is anything in them to express. The mistake we make is to suppose that imagination is fed by nature, or that it works on the insipid diet of children’s story-books. Let a child have the meat he requires in his history readings, and in the literature which naturally gathers round this history, and imagination will bestir itself without any help of ours; the child will live out in detail a thousand scenes of which he only gets the merest hint.”

Geography enhances a child’s appreciation of other cultures.

Though students in Miss Mason’s programmes spent their history studies in Western Civilization, the students gained an appreciation of other cultures through their Geography studies which consisted of living stories. Students did start with their own local area and, through the Forms, moved outward to study the world. Students also read about other cultures in their free readings. I wanted to bring up this point for those who may be wondering how non-Western civilizations were approached in a Charlotte Mason education.

For further study, I HIGHLY recommend this podcast and this article.

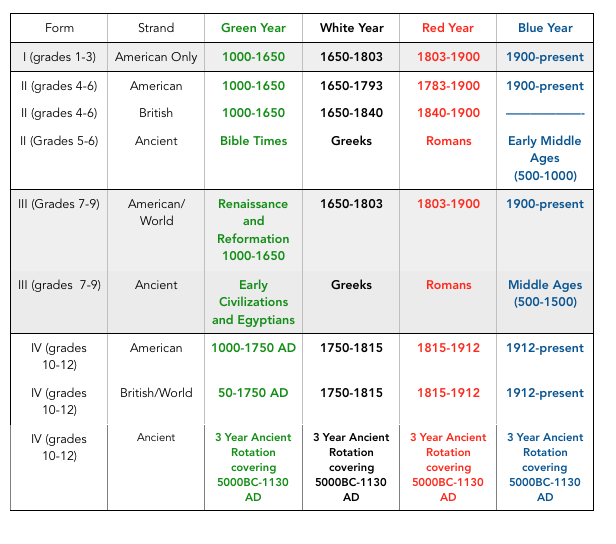

Here is how I interpreted Miss Mason’s history rotations for A Gentle Feast.

I was pleased after reading Miss Mason’s history plan and philosophy. As a former school teacher, I think this approach takes advantage of the natural stages of child development while firmly upholding the beauty and splendor of history. This is truly a nourishing feast of living ideas, people, and places from which the child may digest.

Julie,

Thanks for all the work you’ve put into sharing your plans. They look do able and I’m considering shifting our large homeschool over to Gentle Feast . What are your thoughts/plans on additional science studies? The natural science lesson once a week seems shy of the recommended coursework hours for high school graduation. I appreciate your thoughts on the matter.

Thank you!

Hey Amy,

I completely agree about high school science! In the packet, it is listed as a subject you would need to add into the weekly plans. I didn’t include science (other than natural history for all forms) because it is such an intimidating subject for many. Many homeschoolers I know use co-ops or dual enrollment for high school science courses. If you are wanting to do a completely CM approach, I would highly recommend looking at sabbath mood homeschool’s science guides. This was a subject I wasn’t prepared to teach at home, so my two high schoolers have taken science at a coop. I have found this to work really well for our family as I don’t have access to specialized equipment on my own and my girls can do the labs at coop. I then supplement this textbook work with living books and the natural history. I hope that helps. Please let me know if I can be of any more assistance.

Hi Julie. I have form 2 and form 3. By daughter will be in 6th next year however she has always schooled with her brother and is ready for form 3. In our current rotation (which is just 1 stream) we would be moving to ancients next year. If we were to move over to Gentle Feast form 3 White year would you recommend our 2nd stream of history to start with Middle Ages as written?

Hey Tami,

Thank you for your question. I actually updated the History rotation to make it 4 years so that all forms would have the same Ancient history stream as well. The current student packets for the white year contain what will become the green and white years in the future. My plan is to have all packets available by May 2017. I hope that helps.

Thanks Julie. For those of us that already own the white year (form 2 and 3) will we be able to update?

Yes. I am working on that this week. You should get an email from me soon:)!

Hello there Julie,

I love what you have done here and am seriously considering starting up in January with form 1 and 2. We started off this year in the same time period(green and white),so some would be a review, but it would be minimal. I guess my question is this: How are you faring with this curriculum? Is it gentle yet strong? Overwhelming in the time department? Easily implemented? I started off a nazi homeschool mom, thinking that learning was checking off boxes. I have since done a complete turn around by God’s mercy alone and am very gentle, I know we need to add more, but I need it to work too. I desire for us to work mostly together, but my two little lads have the smallest attention spans ever created. They are slowly learning to love books, but an endless supply might indeed kill them. Haha, I’m obviously long winded tonight. My last question, is there a sample of the phonics? I would love to check it out as I would be ordering that along with the two other packets. Thank you much!

Hello Sarah,

Thank you for your question. The only student packet I have currently available, is a condensed green/white year and it sounds like that would be a perfect fit for what you have currently been studying. I wouldn’t start back at the beginning of the year though, you could certainly start with Term 2 in January and move forward from there. I can totally relate to being a check the box nazi:). I want to empower you that this is more like a buffet. Everything is very delicious, but there is no need to sample everything all at once. Take what you can, being guided by the pace of your children and trust that they are getting a variety of living ideas. This has been a great lesson for me. It has truly changed our homeschool and my relationship with my children. I am excited to present this feast (I’m enjoying learning with them) and I am learning to trust my children to do the hard work of their education by assimilating what they need in any given lesson. Our first term exams went very well, and I was blown away but all the ideas and knowledge my children had made their own using Charlotte Mason’s methods and the books I had planned out. Start small and add on what feels good for your family.

I did decided to split these plans into two years, as I wanted to stay more in line with Miss Mason’s page recommendations (especially in the older forms) and have the ancient history streams line up. So I think it would be quite appropriate to take the condensed year and work at your own pace. I hope this answers your question. Please let me know if I can be of any more assistance.

Oh, and I will add a phonics sample to the product page. Thanks for asking!

Hello!

I am a public school teacher. I will be teaching my 4th grade class online for a portion or all of the year. We have formed a learning pod for my 5th grade daughter and her 2 friends. We have hired a college student who did her student teaching with me, to facilitate their learning in large part. I know that she will do a great job. My concern is where to start. As you may know, 5th grade, in the public schools focuses on US history. I’m not sure if we should use book 1, or 2???? My gut tells me to start with book 1, but you may have a different idea? Thank you for any input you can give.

Yes, start with Cycle 1.